For private schools at the bottom of the pyramid, school closures due to COVID-19 and its economic consequences will pose a serious challenge

COVID19 Impact on School Continuity

“This is the worst crisis my school has seen in twenty years,” says Mohammed Shafi, who runs Monarch High School, in Hyderabad’s Madannapet area. He had to shut down his school of 567 students on the 22nd March as Telangana went into lockdown. Shafi’s school is one of the city’s many private schools serving low-income communities, with fees ranging from ₹ 12,000 – 16,000 per annum. Private schools decide fees based on students’ age and family’s capacity to pay. Most low-fee schools collect fees in a staggered way – through smaller monthly fees as well as larger milestone-linked payments for examinations and admissions. The lockdown thus came at a particularly unfortunate time in these schools’ fee cycle when a sizable proportion of dues from the past academic year are collected.

An exploratory survey conducted by Central Square Foundation across seven states[1], finds acute financial challenges due to COVID-19 among low fee schools. None of the schools surveyed collected fees during the lockdown in April and May, and over half of them have uncollected dues pending from the previous year, amounting to between 13% and 80% of their annual revenue.

Various state governments have introduced fee moratoriums or waivers or requested schools to reduce or forego fees as a relief to parents. Some states including Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra ordered schools to refrain from collecting fees during the lockdown, forcing schools to forgo a large share of their annual fees and not just the monthly fee for March and April[2]. Maharashtra warned schools of strict action if schools withheld staff salaries during the lockdown[3]. With reduced fee collection and Government orders instructing schools to pay wages, school leaders were in a bind.

An exploratory survey conducted by Central Square Foundation across seven states 14, finds acute financial challenges due to COVID-19 among low fee schools.

Vikas Jhunjhunwala, who runs Sunshine Schools in Delhi and Ghaziabad, has three key liabilities – rent, teacher salaries, and textbooks for the next year, which he had bought on credit in March. Only 3-4% of parents are paying for textbooks at the moment. He has not been able to pay rent for one school building for March, April and May; and not been able to pay teacher salaries for April and May. “Teacher salary backpay is likely to be a difficult conversation,” he admits, especially because he knows that parents will be in no position to pay lump sum fees at the end of the lockdown. Nearly 50% of school leaders are considering a shift in pricing models in the upcoming year, with fee discounts or deferrals, pay cuts for staff and increasing class sizes as possible ideas. Our survey finds that nearly half the teachers didn’t receive their salary for March, despite schools closing only in mid-March, and less than a fifth of teachers continued to receive their salaries post-March.

Nearly 50% of school leaders are considering a shift in pricing models in the upcoming year, with fee discounts or deferrals, pay cuts for staff and increasing class sizes as possible ideas.

Though schools are focused on survival through the lockdown, the path to recovery after it is presently ambiguous. Schools at the bottom of the pyramid are very concerned about student attrition due to financial distress and rural migration even after the lockdown lifts. B. Sunitha Kumari who runs St. Alberts School in Hyderabad’s Attapur area estimates that 30% of her students have migrated out of the city, and Shafi predicts that many parents will try to move their children to free schools[5]. Almost a third of parents surveyed reported that they might not send their children to the same school next academic year[6] and some might enrol their children in government schools for this academic year. Several state governments have already reported an increase in admission in government schools[7]. In the medium term, as the lockdown lifts, many private schools with particularly badly affected families may find it difficult to sustain. The private schooling sector will undoubtedly see shifts and short term shrinkage.

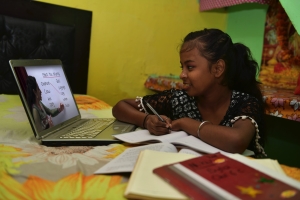

Transition to Online Learning

Despite their uncertainty, school owners want to restore a sense of normalcy for students by exploring online learning. According to a survey by Global School Leaders, 82% of Indian school leaders feel responsible for ensuring the welfare of their students during the crisis. Additionally, many schools are trying to continue to provide value to parents through online learning. More than 2/3rd of schools surveyed have begun to use grade-wise Whatsapp groups to send learning materials to families. About a third of schools have attempted online live classes but report lack of bandwidth or continuous device access for online video classes. Shafi explains that in a class of 40 students, 8 families don’t have smartphones, 5 have data challenges, and families with multiple children have competing demands from different assignments and groups. Vikas is focused on retraining teachers to liaise actively with struggling parents to identify ways in which schools can add value and guide them through at-home education – almost like ‘therapists’, he says.

Our survey finds that a key barrier to online learning is the lack of direct teacher interaction which limits immediate feedback, often affecting slow learners and younger children the most. Many service providers are supporting schools through this process – like Saarthi, a nonprofit that works directly with families, or Varthana and Alokit, ecosystem players who have been curating content for schools they work with.To identify innovative solutions around these issues and disperse them, Alokit hosts theme-based weekly brainstorm video calls and webinars with school owners which touches on aspects of financial management and online education.

Our survey finds that a key barrier to online learning is the lack of direct teacher interaction which limits immediate feedback, often affecting slow learners and younger children the most.

Despite patchy success, an important green shoot that has emerged in this period has been digital experimentation within schools. Our survey finds that service providers to schools across the board have developed and iterated around rough digital solutions to extend support to schools, and rapid trial and error has led to clearer product insights. However, access to schools at scale is a challenge for service providers, and their widespread distribution should be a key goal for organizations trying to catalyze improvement in this sector.

Path to Recovery

As schools stay closed month after month, credit access may be critical for schools to stay afloat. The sector is likely to shrink based on student migration and school closure. Access to low-interest working capital infusions for schools will be challenging – especially since they are not classified as micro, small, or medium enterprises and are therefore ineligible for government credit guarantee schemes. Jhunjhunwala explains that loan-seeking for working capital is rare among schools in his network, since, in normal times, they are able to get a good proportion of their revenue in advance of the period of delivery of schooling. During the present crisis, private school focused non-banking finance company Varthana has seen a growth in interest for working capital loans from school owners. However, in terms of the supply side for loans, they are concerned that the threat of non-performing assets will make new entrant finance companies increasingly conservative towards lending to schools.

Regulatory reforms have been proposed across sectors to build healthier norms post COVID-19, and it is urgent now to think about structural change in the private school sector that will build resilience and encourage quality. This crisis provides an opportunity to open up the sector, by making entry and operations easier, as well as direct policy tools towards learning improvement by way of standardised measurement and dissemination of learning outcomes. The last wave of private school growth caught India unawares – the next one should be planned for. Regulatory tweaks in this period must be designed to enable a new generation of entrepreneurs to better deliver quality across the pyramid, and allow for a healthier, more transparent sector to evolve.