Since 2010, at least 96% children between the ages of 6 and 14 have enrolled into schools in India and yet, according to the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2018, there is hardly any improvement in learning levels, especially at the upper primary level. One out of every four children leaves class 8 without even basic reading skills. Just providing access to the school building is not enough if we want our school-goers to become empowered world citizens of tomorrow. Quality education isn’t just a right, it is also a necessity for a good future for the child, and eventually for the well-being of the whole community.

One of the key questions in education today is around how we can provide quality education to our children. With over 30 years of experience in the area of education management, Dr Jayshree Oza, Advisor, Central Square Foundation, is ideally placed to provide some answers. Prior to CSF, Dr Oza led the Technical Cooperation Agency (TCA) to the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) and the central institutions of National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) and National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration (NIEPA) for nine years, and founded and directed Centre for Education Management and Development (CEMD).

First of all, how do we define quality education – and who gets to decide that?

In any ecosystem, ultimately the recipient of a service determines the quality of the product delivered. There are many recipients in the education system – students, parents, future employers and the society at large – and they all assess the quality of education from their own prism. At the first step, it is the parent of the child who assesses the quality of education his or her ward receives.

Studies show that parents who truly cannot afford private schools are willing to shell out up to 20% of the family income on what they perceive as ‘quality education’, which is basically defined by them solely on two factors: provision of English language teaching and having one teacher per class. This may not be a complete definition of quality education, but it is surely aspirational for the parents!

The educators and the system, we have not done a good job of helping parents and the community define quality education. There is a need to educate people about what good education for their child actually is, while also valuing their aspirational goals for their wards. For example, how learning in the mother tongue is beneficial for a child or how understanding foundational concepts is easier in the home language.

Equally important is strong language learning in the early grades. Research suggests that children who are not able to read with meaning by the time they complete grade 3 often do not succeed in future learning. Reading is an entry skill to the world of knowledge. Children who cannot express themselves in speaking and/or in writing are surely at disadvantage to achieve success in life. So, public view and opinion needs to be formed to this end, among other priorities.

Most children in India now have access to schools but this does not translate into accessing quality education. What are we missing and how do we plug those gaps?

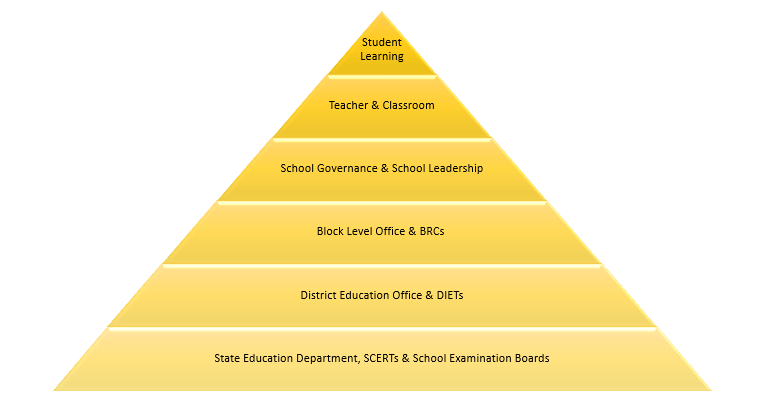

We have made a lot of progress on infrastructure in last 25 years, sometimes making our schools too small! However, now we need to shift our targets from ‘accessing’ to ‘learning’. There is a need for systemic overhaul. Currently, the education system is a pyramid that goes from national level to state to district to sub-district, down to each school. Ideally, this should be turned on its head – start with the child and his/her learning as the top priority. Keep the child at the centre, then classroom, then school, and so on. The question at the state level should be – what do different districts need to make effective schools? The district should ask what schools need to ensure students’ learning and plan accordingly to convey it to the state, and that is how information should flow for the system to be able to make the right provisions.

In a country as large and diverse as ours, one size cannot fit all. Different districts and locations have different requirements and priorities, so these need to be addressed at each level. For example, one teacher cannot teach 40 students of different age groups and at different learning levels. The system must ask itself if creating too many small schools has compromised teacher provision. A school with 200 students can have five teachers and then divide children into 4-5 groups by age and/or learning levels.

Is this kind of systemic change even possible?

Most certainly. Studies and work done by CEMD, TCA and others make it clear that people do know their problems, and can solve their problems through meaningful participation with the people they work with or with those who have expectations from them. They need expert support in facilitating this process and also some tools and techniques that can make it easy for them to address their problems. Help could come in the form of participative research, training and workshops, technical guidance, and partnerships and coalition-building with other professionals and institutions.

An important aspect is respecting individual perspectives while making them part of the process, which is likely to increase their ownership in solving the problems. Change strategies must build knowledge, interest and commitment among staff at all levels. Senior leaders in the system should model the practices and relationships they wish to develop throughout the system. Building trust among people for new technologies and processes in the initial phase takes long, but once trust is built, it becomes easy to implement the rest of the interventions and create change.

Change is a slow process, but not doing anything is not an option. It requires long-term continuous engagement of all key players in the system. Change also brings resistance, especially from those in existing power positions, who perceive a sense of loss in the changed circumstances. It is essential to keep in mind the emotional response to change with all stakeholders, and build that into the process as a key variable.

The system as a whole should focus on what is needed for a child’s learning.

But with whom does the eventual responsibility lie?

That would have to be with every individual in the system. Organizational change begins with individuals. The individual is accountable to the systems’ leaders and that authority should be used judiciously. Every individual’s own sense of integrity and power of reflection should be allowed to develop. This is essential to initiate and sustain change processes.

How do nonprofits like CSF and others help in this process?

Such organizations need a multi-pronged strategy to engage with the education system. The elements of this engagement can be meaningful changes in the classroom processes, content of learning based on desired outcomes, school governance, monitoring and support coupled with accountability, creating demand through advocacy, and using best practices from around the world in a context-friendly and iterative manner. This engagement should be schematic and synchronized to achieve best results.

What will an ideal scenario look like? If you were to narrow it down, what is that one thing we are trying to achieve here?

In an ideal scenario, the system as a whole would focus on what is needed for the child’s learning and ensuring that all children grow to their full potential. We need to build capacity at all levels of the system, starting from the teacher, and also empower them to challenge each other to create enabling conditions so that all children learn. Empowerment and accountability go hand-in-hand. Ultimately, we want to reach the point where the entire system is galvanized towards answering the question: ‘How can I help the child learn better?’