Good data is a pre-requisite for decision-making by governments. Huge volumes of data are generated by the government on a daily basis. But is the generated data reliable? A study by Abhijeet Singh found that student achievement levels in a state-led census assessment were exaggerated when compared to retests conducted by an independent third party. A study by Johnson and Parrado showed that NAS 2017 state averages were significantly higher than both ASER and IHDS averages by comparing common competencies across all three surveys. In addition, the researchers found that state rankings based on NAS data displayed almost no correlation with state rankings based on Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), India Human Development Survey (IHDS), or net state domestic product per capita.

In this article, we focus on student learning data. We look at the evidence that suggests current learning outcome data is not robust, deep dive on the possible reasons for this and then explore phone assessments as a potential model to improve reliability of learning outcome data.

Why is data misreporting happening? It could be because nobody in the education system has any incentives to report true student performance. On the contrary, there is certainly a fear of adverse consequences if bad performance is reported, and a desire to look good by reporting good performance. At the same time, actually improving student performance is a difficult process, especially without adequate levels of support in pedagogy and professional development from the system. The easy way out, therefore, is to inflate data to signal that students, and therefore teachers and other officials, are performing well.

There are two major policy implications from such inflated data. First, there is a possibility of poor designing and targeting of interventions. Let us understand this better through the example of remedial programs. Assessments run by states are used to identify students who are falling behind expected learning levels and remedial programs are organized for them (e.g Mission Vidya). If the assessment data used to identify students who are below expected learning levels is unreliable, the initiative could miss out on many students who are in need of remedial support.

Second, there might be weak accountability across the system, preventing adequate focus on the outcome that we want – learning. Instead, teachers are held accountable for other things, like finishing syllabus on time, ensuring that data collection happens, or delivery of mid day meals.

Set in this context, it is critical to reimagine ways to generate reliable datasets. We can work with the government on systemic changes to ensure data reporting is rigorous. In this case, we can take a leaf out of the Aspirational Districts Program playbook. NITI Aayog developed the ‘Champions of Change Dashboard’ to monitor and review progress of Aspirational Districts. The data used in the dashboard comes from a range of administrative sources. On a quarterly basis, this data is verified by corroborating it with data collected from third party survey agencies to validate critical data points at the district level.

Parallel datasets generated by third party agencies could act as independent sources of truth and could be compared with the state generated datasets. These parallel datasets need not be as large as the census assessments conducted by states; a sample assessment, like a household survey, also has the potential to cross check the quality of state generated data. A source of economical, quick, legitimate and trustworthy data is missing and filling this void is of utmost importance.

Potential of phone assessments

The trend of increased smartphone sales point to the higher penetration and usage of mobile phones in India This presents an opportunity to reach out to children directly to assess their learning levels through phone, without worrying about the physical accessibility to remote geographies. During the pandemic, several initiatives were undertaken to explore the option of assessing children over the phone.

Our hypothesis is that assessing children over a phone call on a sample basis can provide an alternative source to triangulate the data reported by the system and, thereby, improve its reliability. But first, this requires us to check whether phone based data can generate valid and reliable estimates of student learning at all!

To test this, Central Square Foundation, along with Saloni Gupta from Columbia University and Rocket Learning, conducted a pilot to understand if phone as a mode can be used to generate valid and reliable data on learning levels of children compared to in-person assessments. We conducted a pilot with 1603 public school students of Grade 2 and 3 in two districts of Lucknow and Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh.

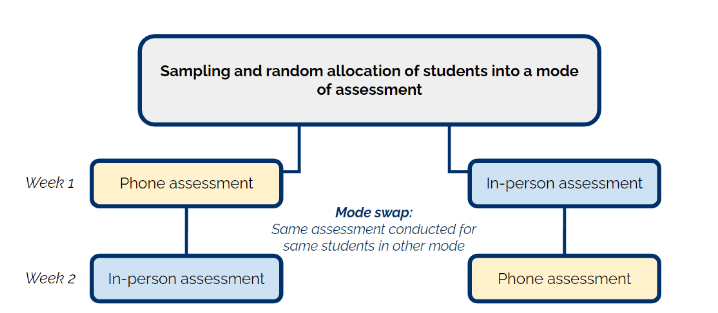

In the first week, half of the students were tested over the phone and the other half were tested in-person. As an important design consideration, we ensured that the sample of children assessed on phone were also assessed in-person within a week and vice-versa. This design helped us in making an apples to apples comparison between the two modes of assessment. Repeating the same test in different order of modes ensured that any effect of familiarity of the test in the first week cancels out in the second week for both modes.

Students were tested by surveyors from an independent agency. All questions were orally administered over phone and in-person. For literacy questions, visual aids were required to test skills such as picture comprehension and reading fluency. For assessments conducted over phone, this was done by using the students language textbook or sending questions as images over whatsapp wherever smartphones were available with the parent. During the corresponding in-person testing of students, the surveyors carried print outs of all the literacy questions for students tested using whatsapp and used the textbook for other students. It took on average 20 minutes to finish an assessment over the phone; it took an additional 10 minutes to build rapport and to collect demographic information about the student.

All 1603 students were given an opportunity to be assessed in both modes. A total of 449 students were assessed in both modes; 161 students were assessed only by phone, and 215 were assessed only in-person. Through this small pilot, we found that phone assessments are valid and reliable for measuring Foundational Literacy and Numeracy skills of students; performance of students on assessments conducted over phone and in-person did not differ by subject, class or question.

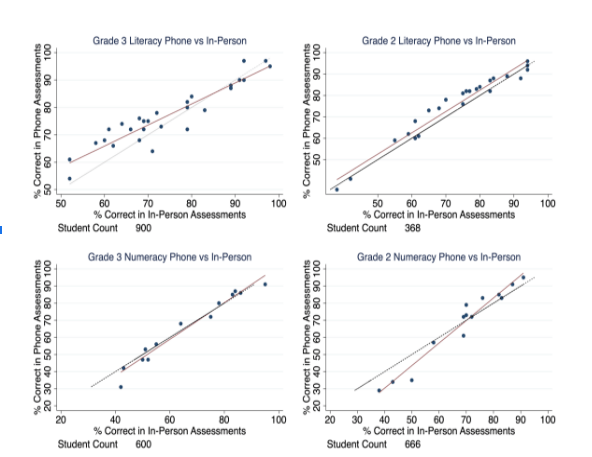

The y-axis in the figure above represents the percentage of students who got a particular question correct on the phone and the x-axis represents the percentage of students who got the question correct in-person. The 45 degree grey line signifies that the performance of a particular student is same in both the modes. Moreover, as seen in the figure above, the line of fit (i.e the red line) is very close to the 45 degree grey line for questions across all grades. This shows that the aggregate performance of students on individual questions is similar across tests conducted over phone and in-person. Our analysis also showed that the majority of students performed at the same percentile rank on phone and in-person.

We also had numerous operational learnings in the process. First, there was high student attrition at different stages of the process. Common reasons for attrition included, but not limited to, incorrect phone numbers/phone being not reachable, textbook not available, consent not given by parents etc. This could be mitigated by using government databases that are regularly updated.

Second, sharing visual stimuli for literacy questions over Whatsapp works better than using textbooks. We found that, in many instances, students had rote memorized passages from the textbook. Moreover, torn pages and unavailable textbooks further added to the complexity.

Third, we found a 12% higher incidence of prompting over phone than in-person assessment. We are exploring ways to reduce incidence of prompting, but while it is a concern, it is important to note that it is significantly lower than the inflation found in system generated data.

Now we want to leverage our learnings from the small pilot to check if phone assessments are technologically feasible, financially viable and administratively doable.

A large and professional call center industry is a strength that India can leverage for phone assessments. In fact, call center infrastructure already exists with many state governments. We believe that phone assessments would provide state governments a cost-effective option of independently generating data that they can then compare with data generated by the school system. It can help them improve data quality and usher in a culture of honest data reporting across the government system.