Teachers play the most critical role in helping children learn meaningfully. Decades of research[1] has found that an effective teacher can boost children’s learning by 1.5 grade level equivalents, while a struggling teacher only gets half an academic year’s worth out of their students. Raising teacher effectiveness is critical if we want India’s school-going children to master the basic academic concepts and thinking skills needed to succeed in later life. India has set itself an ambitious goal to achieve universal Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN) by 2025, by ensuring that every child is able to read with meaning and solve basic math problems at the end of grade 3. Teachers will play an extremely crucial role in helping the country to achieve this goal.

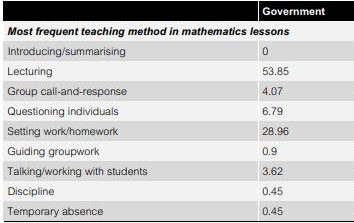

However, efforts to improve teacher effectiveness have not yielded visible results. The government has taken several steps, including improving teacher salaries[2] and introducing portals like NISHTHA to build teacher capacity. However, teachers remain burdened with administrative tasks[3], leaving them with little time to prepare lessons. More significantly, pre and in-service training[4] fail to train them on the practical application of subject knowledge and pedagogical techniques that can potentially improve classroom teaching. Consequently, teachers enter classrooms without the skills of delivering engaging and rigorous instruction. The Young Lives School Survey, Andhra Pradesh, 2010-11 highlights that lecturing is the predominant mode of teaching, as presented below[5]:

Source: Young Lives School Survey, Andhra Pradesh, 2010-11

Structured Pedagogy: A Scientific Approach to Teaching Foundational Skills

Contrary to popular opinion, teaching is a highly complex and demanding job. If this seems hard to believe, try sitting in a classroom and keeping thirty energetic young children engaged in learning for thirty minutes! Research shows that on an average, elementary school teachers have 200 to 300 exchanges with students every hour (and between 1,200 to 1,500 exchanges in a day)[6]. This level of cognitive complexity is equivalent to that required of highly skilled professionals like doctors, engineers, or lawyers. So then, why are teachers not prepared with the same rigorous approach as their peers in other domains?

What if every teacher could identify the specific learning goals that each of their children can accomplish, in the same way as a lawyer understands the framework of the Constitution? What if we could train all teachers to take a step-by-step approach to teaching reading or subtraction, with the same precision that an engineer follows while building a semiconductor chip? What if an expert literacy coach could demonstrate an effective ‘read-aloud’ in the classroom, much like a senior surgeon demonstrates how to treat a trauma wound to medical residents? This is precisely what a ‘Structured Pedagogy’ approach does – it is a scientific, evidence-based, learner-centered approach to teaching that equips every teacher with clearly defined objectives, proven methods, well-structured tools, and practical training. Such a scientific approach has been proven to work for teaching foundational literacy and numeracy skills in children.

The goal of good literacy instruction is to ensure that all children are able to read on their own, at the right pace, and make meaning. Research on successful literacy programs[7] across countries[8] and languages shows that effective reading instruction boils down to five critical skills that need to be systematically and simultaneously built in children:

- Manipulating smallest units of sounds in words (Phonemic Awareness)

- Mapping a sequence of letters to a sequence of sounds in a word (Phonics)

- Reading accurately at an appropriate rate (Fluency)

- Breadth and depth of word understanding (Vocabulary)

- Extracting meaning from text (Comprehension)

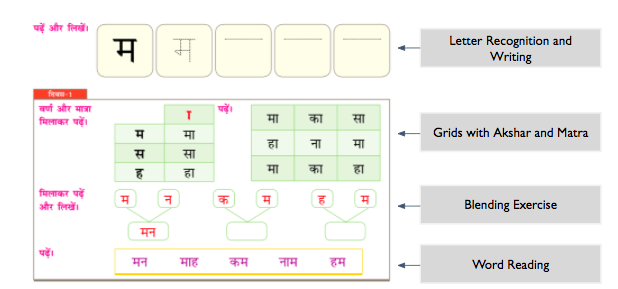

Such a “Balanced Literacy” approach has been tried and tested in India. As shown in this resource drawn from Room to Read, India children are given targeted activities to recognise letters, blend letters into words and read.

Source: Room to Read, India

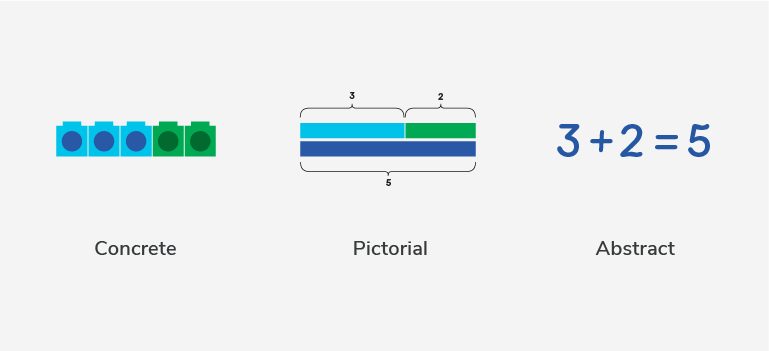

Similarly structured instruction in numeracy progresses from ‘simple to complex’ or ‘known to unknown’[9]. A good way to do this is to follow the ‘Concrete-Pictorial-Abstract’ approach. For instance, the teaching of addition can be broken in three phases where the learning gradually progresses from the use of concrete objects to pictorial representations and finally the use of symbols. Use of manipulatives (mathematical toys) also ensures that children learn through hands-on experiences and are actively engaged.

Source: Math, No Problem

A Tightly-Knit Teacher Toolkit is Needed to Implement Structured Pedagogy

A ‘tightly knit teaching toolkit’, where teachers are provided with an ecosystem of linked teaching-learning resources is essential to implement structured pedagogy in the classroom. Such a toolkit usually include the following critical components:

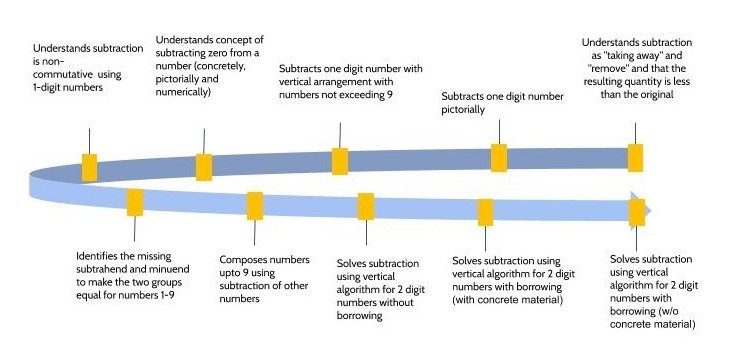

- Learning Outcomes Framework: This framework sharply defines the scope and sequence of ‘micro’ steps that a child needs to acquire a skill. These steps enable a teacher to clearly pinpoint what to focus their teaching on, and identify precisely at which stage learning breaks down for the child. For example, while learning subtraction, a child broadly follows the learning trajectory outlined below:

Source: CSF- CARE Learning Outcome Framework

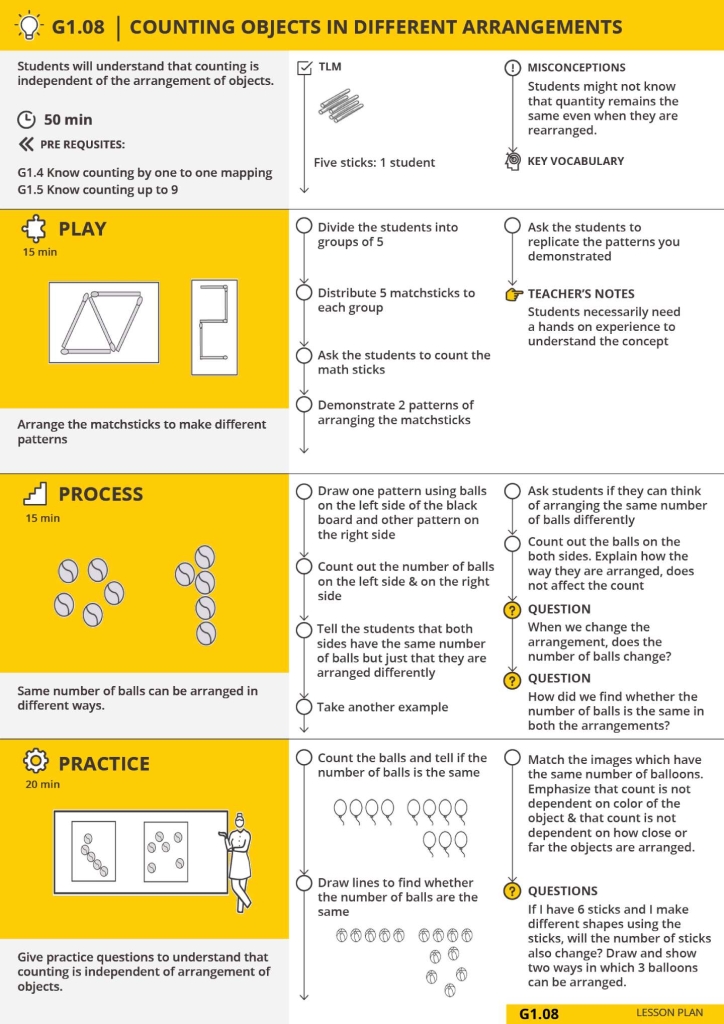

- Teacher Guides and Structured Lesson Plans: A teacher guide contains lesson plans with step-by-step pedagogical routines to guide teachers on conducting effective and engaging lessons linked to the targeted learning outcomes. An effective lesson plan provides a transition from teacher-led to student-led activities in the classroom, notably:

- Teacher Demonstration (I do), where the teacher provides ‘direct instruction’ to the students

- Guided Practice (We do), where students and teachers work together on the learning material. Teachers also give feedback on the students’ work and clarify their misconceptions

- Independent Practice (You do), which gives opportunities for children to apply and reinforce their understanding by solving problems unassisted. As shown in this exemplar lesson plan, teachers find it easy to absorb when the plans are visually engaging, have simple step-by-step instructions, use icons and diagrammatic representations of key conceptual elements. The ‘look and feel’ of these resources should be such that they elicit a feeling of professional pride.

Source: : CSF-CARE Lesson Plan

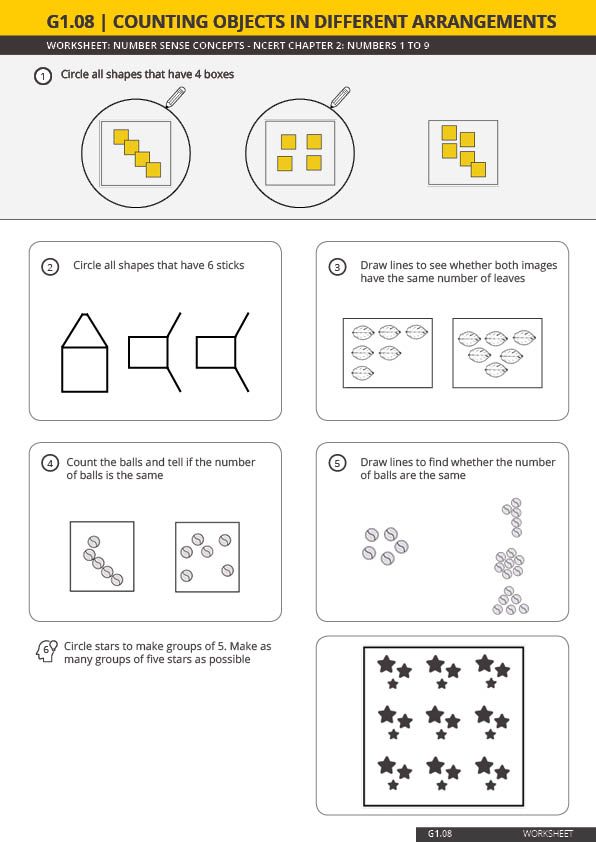

- Student Worksheets & Teaching Learning Materials: Worksheets can be used for strengthening concepts through carefully planned guided and independent practice. Worksheets can be designed for practice to help children practice skills at home, remedial to overcome learning gaps, and as formative assessments to understand progress and seek corrective action. Along with worksheets, Teaching Learning Materials like mathematical toys, big books, posters, story books should also be provided in the classroom to enhance conceptual understanding, improve motivation and engagement

Source: CSF-CARE Worksheet

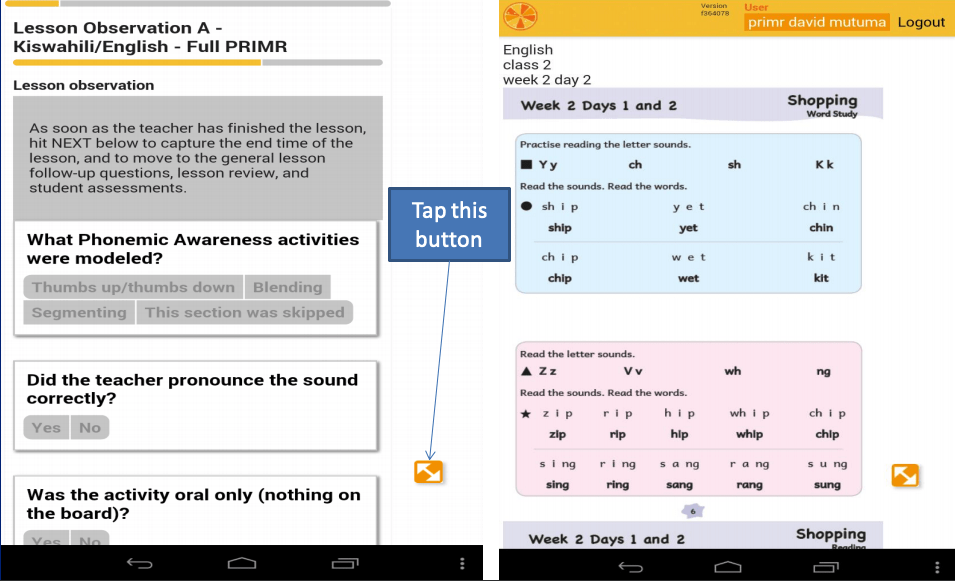

- Teacher Training and Classroom Coaching: The last and the most critical aspect of the structured pedagogy approach is training and coaching teachers specifically on how to use these materials in the classroom. In-classroom coaching by trained ‘master-teachers’ has been shown to be effective in instilling classroom-specific micro-skills and behavior change in teachers. For example, in the Tusome Program (a successful structured pedagogy intervention for improving early grade literacy in Kenya) teacher-coaches travelled to schools to support teachers. They used a mobile app[10] to record teacher practices, assess student learning and monitor use of instructional resources. This data was then analyzed to provide remedial support to schools.

Source: Tusome by RTI International implemented in Kenya

Impact and Implementation in the Indian Context

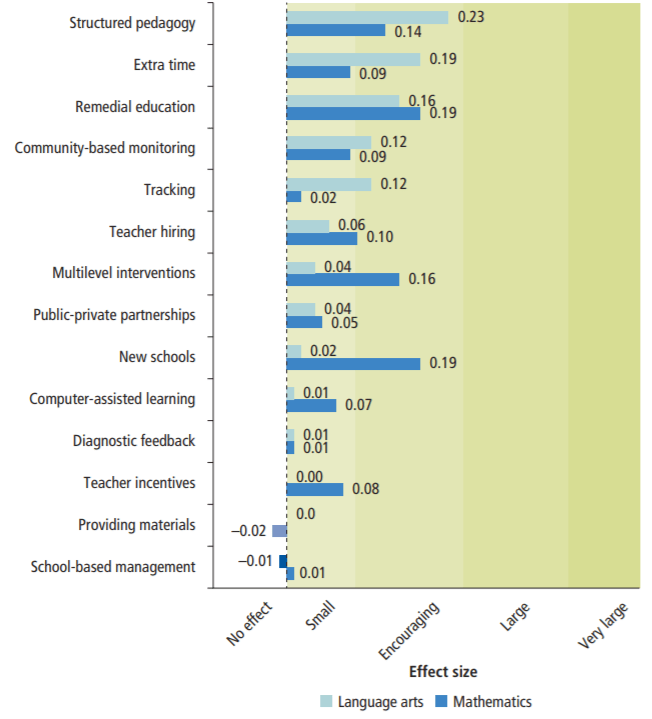

School improvement programs using the structured pedagogy approach have demonstrated a measurable and significant impact on student learning, especially in middle- and low-income countries.[11] This has been reiterated by findings from Papua New Guinea’s randomized Reading Booster Programme[12] and Tusome Early Grade Reading program in Kenya[13]. An important component of the Structured Approach, i.e., teacher guides have also been identified as a cost-effective way to improve learning[14]. In India, non-profit organizations such as Room to Read in Madhya Pradesh and Language and Learning Foundation in Haryana adopted the structured pedagogy approach and have shown strong gains in student learning outcomes[15] in early grade literacy.

Source: Facing Forward, World Bank, 2018

However, for the approach to be effective at a large scale, three critical implementation measures are essential. First, curricula, classroom tools, assessments, and training should be tightly linked and enable a coherent support system for teachers. Second, teacher guides should be mapped to the curriculum and textbooks prescribed by the states to ensure that teachers do not hesitate to use them in the classroom. Third, teacher materials should be easy to understand and provide practical guidance on how to teach in an actual classroom context.

Despite strong research evidence in its support, some misgivings regarding the structured pedagogy approach have hindered its adoption. Some critics argue that structured lesson plans kill a teacher’s autonomy. On the contrary, they reduce the cognitive load of deciding ‘what and how’ to teach, focusing the teacher’s attention instead on which students to work with and what kind of support to provide. Others argue that such approaches promote rote-learning and stunt higher-order skills. By using concept-building activities, guided practice and eliciting student understanding, structured pedagogy strengthens understanding and problem solving. By maximising instructional time, systematically focusing on essential skills, making space for independent work, structured pedagogy is a child centric approach – and not teacher-centric as some fear.

A structured pedagogy approach can be a potent tool to empower and support teachers in India, where teaching skill is variant, training opportunities are fewer, and instructional time is less than required. For far too long, we have blamed teachers for the failures of the Indian education system, labeling them as under-motivated or unskilled. The work of teaching is dismissed as an ‘art form’ that defies scientific definition and rigorous process. These erroneous assumptions only serve to undermine the role of teachers, creating a sense of hopelessness. The adoption of structured pedagogical practices in Indian classrooms will allow us to shift the narrative away from labelling ‘teach-ers’ towards demystifying the act of ‘teach-ing.’