School disruptions in the last few months owing to COVID-19 is suspected to have aggravated the learning crisis in India. After having achieved near universal student enrollment in primary schools, which is no small feat in itself, several states in the country were announcing concrete steps to improve learning outcomes when the pandemic struck. India is faced with an unprecedented situation — from policymakers, to NGOs and CSOs working in the education domain, to philanthropists, we need to act collectively to ensure that our efforts to improve access and provide quality education do not get undone.

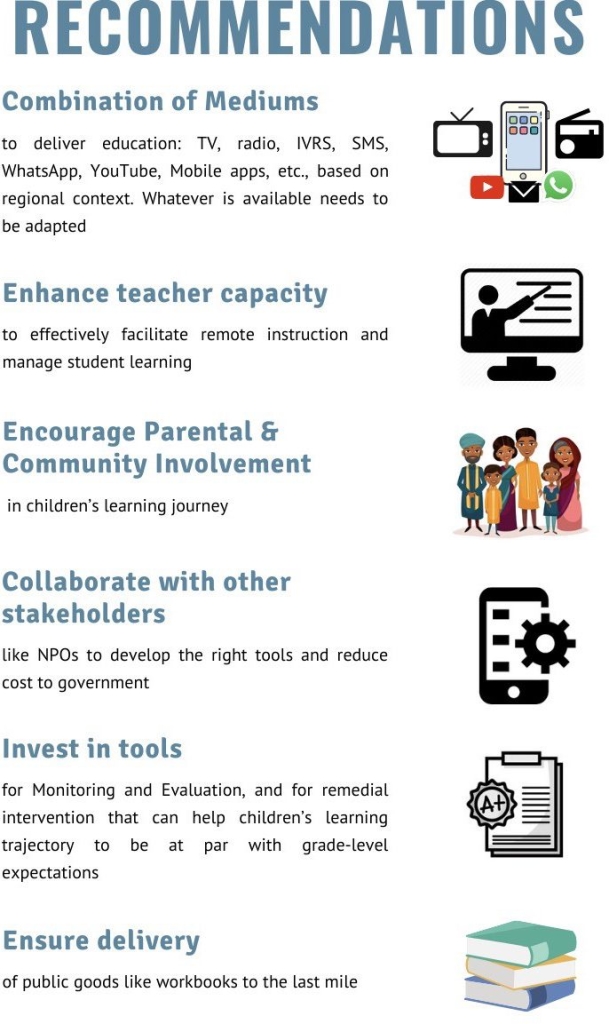

CSF consulted leaders and experts from non-profits, academia, and the government to arrive at certain priority areas for the education sector as we move towards the ‘new normal’. Regardless of whether school reopening is staggered or home learning continues for longer, the following areas need to be the focus. Moreover, children’s health, nutrition and mental well-being must be kept at the centre while drawing up the plans.

1. Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN)

Research suggests that children’s learning during the summer vacations decline by a month’s worth of school-year learning. This is referred to as the ‘Summer Learning Loss’[1]. The current extended school closures owing to the pandemic is likely to similarly widen the learning gap. This was also seen to be the case during the Ebola outbreak across West Africa[2]. What’s worse is that children from marginalised and economically disadvantaged households bear the maximum brunt.

One of the first things schools need to do on reopening is to understand the learning levels of children while ensuring their social and emotional well-being and build from there. This is especially critical for primary school children who are in the midst of acquiring foundational skills — the ability to read with meaning and solve simple math problems. If children fail to acquire these basic skills by Class 3, they tend to fall behind. Their learning curve flattens and it becomes difficult for them to ‘catch up’ in the later years.

As children start going back to school, it would be imperative to break away from ambitious curriculums and a long list of indicators most of which don’t evaluate the quality of learning. We will need a laser sharp focus on FLN to maximise children’s learnings.

The silver lining in the current situation is that perhaps it will compel us to change our approach towards education. As children start going back to school, it would be imperative to break away from ambitious curriculums and a long list of indicators — most of which don’t evaluate the quality of learning. We will need a laser sharp focus on FLN to maximise children’s learnings. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s announcement of launching the FLN Mission by December 2020 comes at an extremely opportune time. For the success of this mission, it will be imperative to identify and define key competencies for each grade like letter recognition, blending or decoding, fluency, and eventually reading with meaning.

2. Remote Learning

The Ministry of Human Resource Development’s flagship EdTech initiative — DIKSHA — has been helping children engage with curriculum aligned content at home. Many states implemented EdTech initiatives specific to their regions for continued learning. Himachal Pradesh launched ‘Har Ghar Pathshala’ wherein they collated learning material on a microsite and used WhatsApp extensively to connect with students and parents. Punjab adopted multiple platforms and solutions including YouTube, TV, and radio to disseminate academic content. Madhya Pradesh launched ‘Hamara Ghar-Hamara Vidyalaya’, a campaign on Doordarshan wherein children between Classes 1-8 will be taught at home in a simulated school-like environment.

Such implementation of EdTech at scale has been unprecedented in India. This has brought to fore several challenges and opportunities that need to be acted upon going forward. One of the main challenges has been the access to electricity, devices, and internet in low-income households. The crisis has exposed the digital divide and exacerbated the learning divide. Moreover, teachers are not well equipped to teach via EdTech at this scale. Therefore, addressing the digital divide to improve access and enhancing teacher capacity are critical.

Accounting for the state’s context can be a determining factor in the efficacy of remote learning. Delivering high-quality content in vernacular languages using a combination of mediums like TV, radio, and IVRS among others can help children learn better. Teachers and parents will have to work together to institute systems that can identify what each child knows, and instruct them according to their level, and not according to the grade they are in. Moreover, increased parental involvement in children’s learning journeys is proven to be helpful.

3. Private Schools

Nearly half of India’s children attend private schools. With household income impacted and financial stress mounting, many children are likely to move to public schools. This is an extremely tricky spot for public as well as private schools. With government expenditure on the education sector likely to be restricted[3], public schools will be hard-pressed to cope with the move. Many private schools, especially low-fee ones that form the bulk of the sector, may be compelled to shut down permanently as parents struggle to pay school fees which makes up for most of their revenue.

After the sudden and prolonged closure of schools, everyone from the government(s) to teachers to parents switched to EdTech for continued learning at home. A preliminary exploratory survey conducted by CSF found that many low-fee private schools struggled with the transition to digital learning due to lack of access highlighted in the earlier section. This has adversely impacted learning levels and widened the learning gaps between children attending high-fee and low-fee schools. Moreover, the majority of parents have been unable to support their children with their learning needs.

Many private schools, especially low-fee ones that form the bulk of the sector, may be compelled to shut down permanently as parents struggle to pay school fees which makes up for most of their revenue.

Given the testing times, the government should consider supporting the private school sector. Much like it has extended financial help to other sectors, the private school sector needs aid too. This crisis could also serve as an inflection point and bring attention to the constraints within which the sector currently operates, and the reform measures it needs so that children attending private schools can have better learning outcomes.

While the crisis undeniably poses serious challenges, it also presents us with opportunities to reconsider and streamline our strategy and approach on how we educate our children. In bringing these multiple strands together, the government may perhaps have to take decisions at a systemic level that it may have never even considered before — like extending the school year and pushing admissions by a few months. Or making changes to the existing curriculum with more focus on competency-based learning for this academic year and developing a comprehensive plan to bridge gaps over the next few academic cycles. These measures will ensure that children’s learning levels don’t get impacted beyond the period of crisis. We have been caught unprepared, but let’s not make the mistake of letting our children get through school without actually learning anything. Reorienting and reprioritising can help the education system emerge stronger.