In 2025, what does India’s changing FLN story reveal about its ambitions?

Picture three children entering Grade 1, each decades apart.

In 1955, a child sat cross-legged on a mat, learning through repetition and recitation. In 1995, another arrived at a bustling government school, shaped by mass literacy campaigns and new infrastructure. In 2025, a third walked into a classroom with activity-based learning, structured lesson plans, and a national mission focused on one thing: ensuring every child can read, write, and do basic maths.

These three children are products not only of their schools, but of the stories India told itself about education at each moment. Those stories shaped everything from what got funded, to what got measured, and what got ignored.

Today, India is living through a new story. For the first time, foundational literacy and numeracy (FLN) sits at the centre of the national education agenda. But getting here required traversing a long arc, one that moved, slowly and unevenly, towards a single realisation that schooling without learning was not enough.

Writing in Democracy and Education in 1954, India’s first Vice President, Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan declared, “The future progress of the country depends on accomplishing in a few decades the work of centuries. The essential means of bringing about a new society is education.”

Seven decades later, India is finally positioned to fulfill that vision. The long arc Dr. Radhakrishnan envisioned has taken shape through successive transformations, each building on the last.

The Post-Independence Education Narrative: Remnants of the British Raj

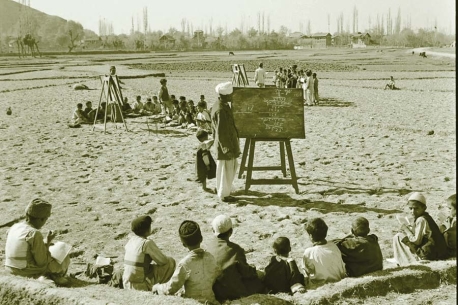

Prior to British rule, India had a vibrant education system where students learned holistically in small groups with personalised attention. Education was imparted outdoors, in small groups or even one-on-one. Many precursors of differentiated learning were prevalent in ancient India.

The British Raj fundamentally reshaped this educational system. Lord Macaulay aimed to modernise India’s education system by adopting Western knowledge and education, particularly the English language. The primary objective was to create “a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions who we govern, a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect.” Inspired by the Prussian K-12 model, this system emphasised rote learning and standardised curriculum over creativity.

There was also higher emphasis on building higher educational institutions to serve imperial interests. The University of Calcutta, University of Bombay, and University of Madras, were established in 1857, which followed the University of London model and focused on producing clerks, administrators, and low-level officers for the colonial state. Elementary education was irrelevant to colonial design.

Post Independence India faced its own challenges. Hon’ble Prime Minister Sh. Jawaharlal Nehru’s vision of rapid industrialisation through Five-Year Plans required trained professionals. But India faced acute shortages. A 1958 International Monetary Fund (IMF) noted that “the shortfall in attaining targets under the First Plan was due as much, if not more, to this factor (lack of trained professionals) as to lack of other resources.”

To solve this the government focussed on improving higher education. The University Education Commission (1948), under Dr. Radhakrishnan, became Independent India’s first education commission and it focused exclusively on reviewing university education. Primary education wasn’t the priority.

The Kothari Commission (1964-66) marked the first major pivot. It acknowledged “the neglect of primary education” and declared “the destiny of India is being shaped in her classrooms.”

Yet this shift remained framed through nation-building. The Commission and the subsequent National Policy on Education (1968) positioned education as essential for creating “young men and women of character and ability committed to national service and development.” The strategy to achieve this was to increase spending on education and expand access through “the early fulfilment of the Directive principle under Article 45 of the Constitution seeking to provide free and compulsory education for all children up to the age of 14.”

However, FLN was not discussed. The system assumed that once enrolled, children would naturally learn.

1980s – 2000s: Literacy as Liberation

The National Policy on Education (NPE) 1986 was the first to articulate the need for “quality” in education. It stated, “The new thrust in elementary education will emphasise two aspects: (i) universal enrolment and universal retention of children up to 14 years of age, and (ii) a substantial improvement in the quality of education.”

It even introduced early versions of what we now call grade-wise competency mapping, promising “minimum levels of learning” for each stage and a shift towards activity-based, child-centred pedagogy.

However, in practice, quality became conflated with inputs. As a response to the recommendations made under NPE 1986, Operation Blackboard was launched in 1987 as a national program to provide minimum essential facilities to all primary schools. The Sarva Shiksha Abhiyaan (2001), followed suit, by expanding schooling rapidly. As a result, school enrollment in primary grades soared and infrastructure boomed. Yet foundational learning remained invisible.

This was India’s expansion era. Ambitious, hopeful, addressing the need for long term solutions yet oblivious to the mounting learning poverty.

ASER and The Age of Data Reckoning

2005 marked a breakthrough. Pratham released its first Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) which revealed the hidden learning crisis. 72% of Grade 3 children could not read a Grade 2 text and 68% could not do subtraction.

A phrase entered India’s education lexicon: “Schooling is not equal to learning.”

However, the Right to Education (RTE) Act 2009 continued on the earlier vision of universal schooling by making free and compulsory education a fundamental right. It ensured access and rights, but it left learning undefined.

Still, something had shifted. The data was out. The crisis was no longer hidden. But turning awareness into action would take another decade.

The Era of Convergence

2014 onwards, something interesting started happening. Decades of separate trajectories, from economic liberalisation, global development frameworks, to mounting evidence of learning failure, were converging.

The story begins in 1991, when India liberalised its economy. Over two decades, economic growth became a defining national narrative. When Sh. Narendra Modi became the Hon’ble Prime Minister in 2014 on a platform of development and economic transformation, sustainable economic growth moved from aspiration to national imperative.

This shift posed a critical question: What kind of education system does a growing economy need?

The answer emerged from global research and Indian reality.

In 2015, India committed to the Sustainable Development Goals, including SGD4, which elevated quality education as a universal imperative, signaling a worldwide pivot towards learning.

Then came 2018. Two watershed moments occurred. The World Bank launched the Human Capital Project, demonstrating that human capital is the most critical component of national wealth and development. Crucially, it measured human capital not by school enrollment, but by “learning adjusted years of schooling.” A few months later, the World Bank and UNESCO introduced the Learning Poverty Indicator, exposing the stark reality that millions of children in developing countries were in school but not learning.

India, as a signatory to these global frameworks, found itself aligned with a worldwide shift from inputs to outcomes, from schooling to learning.

The confluence was complete: economic growth as a national agenda, evidence linking human capital to prosperity, undeniable data on India’s learning crisis, and global momentum toward quality education. The conditions were finally ripe for transformation.

NEP 2020 and the New Era of Education

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 did something unprecedented. It acknowledged the learning crisis by name. For the first time, a national policy stated explicitly that “a large proportion of students currently in elementary school – estimated to be over 5 crore in number – have not attained foundational literacy and numeracy.” And it declared achieving universal FLN an “urgent national mission.”

In 2021, the NIPUN Bharat Mission converted that declaration into action with detailed guidelines, a national curriculum for the foundational stage, dedicated state budgets, and clear targets with accountability mechanisms.

This was a narrative reset for the education system. For the first time, India declared that foundational learning was not a by-product of schooling, it was its purpose. This reset was solidified in 2023 when India hosted the 18th G20 summit. At the Summit, the G20 New Delhi Leaders Declaration recognised “the importance of foundational learning (literacy, numeracy, and socio-emotional skills) as the primary building block for education and employment.” This positioned India as a global voice for FLN.

Vision 2047 and the Road Ahead

The history of India’s education reform shows us that educational progress is not just the product of policy alone. It is shaped by the stories leaders tell, the problems they prioritise, and the identity a nation builds for its education system.

India has spent decades moving from access to quality, from schooling to learning, and now from learning to foundational learning. The launch of NEP 2020 and NIPUN Bharat Mission marks a historic turning point towards a recognition that foundational learning is not optional, but essential.

Moving forward, we have a legacy moment that can transform this Mission into a culture, becoming a defining characteristic of India’s education system. One that becomes woven into the fabric of government at every level and that every child becomes a lifelong learner.

The true measure of success will be this: the child entering Class 1 in 2035 should walk into a system where foundational learning is so deeply embedded, so naturally practiced, that it no longer requires special missions or campaigns.

Between today’s national commitment and tomorrow’s classroom reality lies the last mile where policies meet practice. The NIPUN Bharat Mission has laid the groundwork. Four years of implementation have familiarised the system with new goals, structures and expectations.

The critical work ahead is embedding these practices into the muscle memory of the education system. This will determine whether India builds a high-quality education system by design or inherits one by default, whether foundational learning becomes what schools simply do by choice, or leaves a child’s learning to chance.