Background

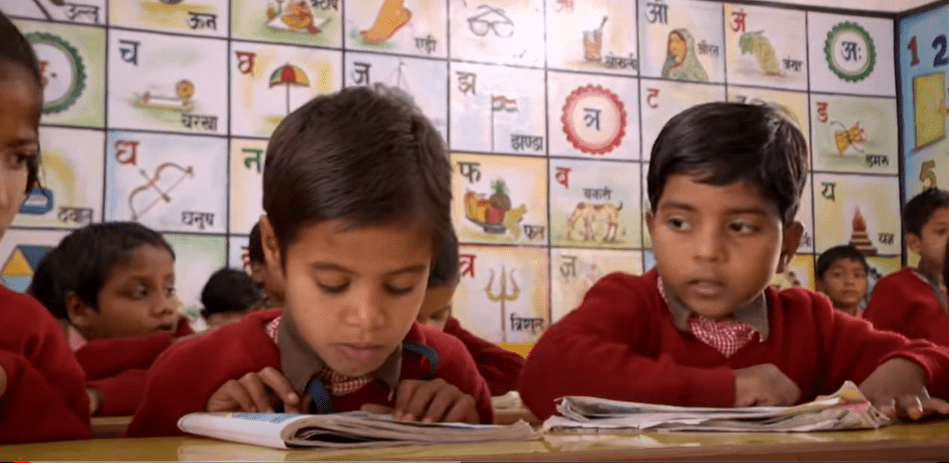

Assessments are critical for planning academic interventions that may be needed to improve the quality of children’s learning. As the sector moves to a results-based framework, both in public sector funding and private action models, it becomes essential for assessments to be conducted in a reliable, cost-effective, and logistically simple manner to have more robust groundwork.

Data is usually captured through two methods- manual and automated. The manual process involves copying data on a document into a digital entry. This process was defined by Cokie and Maxwell (2004) as rekeying; it is time-consuming and needs continuous involvement. For automated processes, one of the most common methods is that of an OMR (Optical Mark Reader), specifically designed for examinations and tests in education (Hamzah 2018).

Punjab, for its baseline assessment, evaluated both the manual and automated processes in the light of the following considerations:

- Large-scale operation: the baseline had to be administered in sample children derived from about eight lakhs students spread across 13,000 primary schools

- Field support: mentors and teachers of government schools were engaged in data capturing, implying heterogeneous awareness of technology (in general) across the field investigators

- Granularity of data: Over 400 different data points were captured per student, item-wise, across three subjects; some tasks even required capturing of the time taken by each student to complete the task.

Given the above factors, while the manual entry format would have made the process tedious and inaccurate, the OMR method would be costly and difficult in capturing extensive data. The legacy systems were untenable and so it was critical to explore new platforms and processes through which this study could be conducted.

To identify the best solution, the following aspects were considered:

- The experience of the state with technology was an advantage, however, Punjabi being the local language directed the evaluation team to identify language integration and operations at scale as focal priorities.

- Types of questions, skip logic, and data exportability were the key areas as recommended in the broad framework for the evaluation by Dickinson et al (2009).

- The nature of data capture was fundamentally different and comprehensive than just capturing the correct answer. EGRA (Early Grade Reading Assessments) and EGMA (Early Grade Mathematics Assessments) standards of RTI were adopted for the study, requiring the data capture to be aligned to the ways it was being asked of the student.

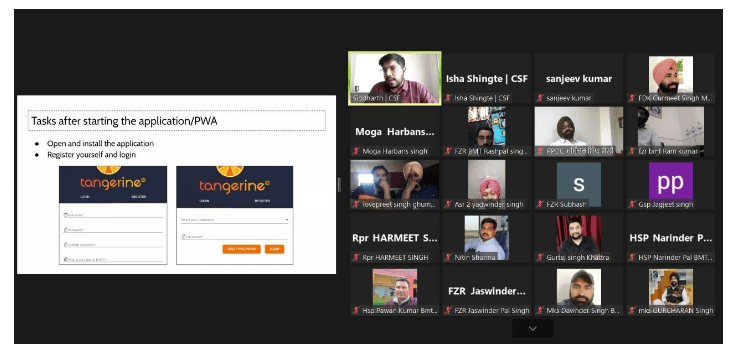

Conventional platforms such as Microsoft Excel and Google Forms, survey tools-KOBO and Collect, and education-specific tools Tangerine and OpenEMIS (Open Education Management Information System) were evaluated. Subsequently, Tangerine was explored further due to its easily operable backend and quick deployment of forms.

Key Aspects of Implementation

(A) Training process

Due to the paucity of time and eminent school closures in Punjab, the training was conducted online. Adopting a new tech platform in an online training format with limited time to understand its nuances was a challenge. However, the familiarity of the state resource persons with basic technology helped in this regard.

(B) Hardware

To prevent any time lag and resource reallocation from the department, the best fit option was to employ the ‘Bring Your Own Device (BYOD)’ Model (Awais et al 2017), wherein the field investigators used their own devices. This, however, required highly nuanced troubleshooting in case of device issues or developing SOPs (standard operating procedures).

(C) Cost and effort

Conducting the assessment and its training in the given model reduced cost and effort in these aspects:

- 96% reduction in pages being printed for the exercise, in comparison to using OMRs

- No additional logistical and processing costs to receive data

- Time taken to conduct the exercise per student was 15-30 mins, against the 1.5 hours needed by the field investigators using OMRs.

Key learnings

Availability of technology is not enough to introduce and implement a new platform. There are several other aspects that need to be considered to ensure state-wide adoption. Mentioned below are some of these aspects:

- Simple and effective tech platform

A technological platform needs to be extremely simple and lean. It should ideally be without any frills, but highly potent and authentic. However, it is important to adjust for any backend snags. On the first day, a server connection issue led to published forms being inactive and syncing was not possible via the android app; this issue did not occur again.

- Government buy-in

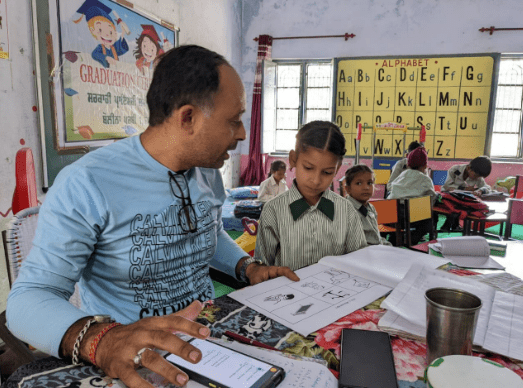

Getting reliable data was the key focus for the state. Hence, a new process was sought. This required taking a plunge into the unknown. Before a full-scale deployment, the state leadership was presented with the usage of the platform with about 10 students, This enabled them to conduct field testing of the tool, affirming trust in the platform and process.

- Clear communication

The process of moving to a new platform needs strong communication of the context, purpose and expected outcomes to build confidence with the field teams, especially among the district leadership. The purpose of the application, the baseline study, and the expected results were clearly communicated by the state leadership.

- Training process

The multiple rounds of training with the field teams emphasized the importance of capturing data on the App in conjunction with administering the assessment. Since both aspects were explained together, they were perceived as complementary functions in conducting the baseline and not as an additional burden for the field investigator.

- Remote support

Conducting a large-scale operation needs a SPOC for clearing doubts that may arise during data collection. A SPOC can ensure consistency in the resolution of doubts and aggregation of any changes to the backend data if any.

- Monitoring

To maximize the effectiveness of the platform, it is essential to monitor the form submissions daily. At the end of the day, data was cleaned for some specific administrative variables such as school name, field investigator details, time of the day, etc. This helped in supporting district-level planning for forthcoming days.

Conclusion

Tangerine’s contextualization and effective utilization by public school mentors and teachers gave a boost to the adoption of technology in the education system. This opens new horizons for conducting systemic assessments, spot assessments, and monitoring.

Conducting student assessments in a cost-effective manner, with minimal administrative burden, is a critical component in generating data to drive decision-making at all levels. In this case, technology simplified this process, and the state moved a step forward in its mission to achieve foundational learning for all students.

Post Punjab’s experience, other states like Telangana, Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh have used Tangerine to conduct similar state baselines. This goes on to validate that technology is agnostic to new territories, contextualization being the necessary condition for it.